Frida Kahlo, $55 Million, and the Bed Where the Work Was Made

A Frida Kahlo painting just sold for $55 million, and instead of thinking about money, I thought about a bed.

Not a metaphorical bed. Not an imagined one. Her actual bed—the one sitting quietly in her house in Coyoacán, now the Blue House museum. The one visitors shuffle past slowly, instinctively lowering their voices. The one where so much of her work began, not because she wanted to paint there, but because her body left her very few other options.

Photo and caption copied from nytimes.com: Frida Kahlo, “El sueño (La cama),” or “The dream (The bed),” from 1940, brings the artist’s preoccupation with the border between sleep and death into focus.Credit...Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via Sotheby’s

The painting, El sueño (La cama)—The Dream (The Bed)—was made in 1940, one of the most turbulent years of Frida Kahlo’s life. Her health was unraveling. Her marriage to Diego Rivera was once again in crisis. The painting shows her asleep beneath a canopy bed, vines creeping around her, a papier-mâché skeleton smiling overhead. It’s quiet. Haunting. Less confrontational than many of her self-portraits. She isn’t staring us down. She’s horizontal. Vulnerable. Somewhere between rest and disappearance.

That painting sold at Sotheby’s after just four minutes of bidding. Fifty-five million dollars. A record for Kahlo. A record for a Latin American artist. Just shy of the inflation-adjusted record for a female artist overall.

And still, I keep coming back to the bed.

Standing at the Foot of Frida Kahlo’s Bed

Frida Kahlo’s bed at the Blue House in Coyoacán, Mexico.

This is where she spent long periods of her life—and where many of her paintings began.

When I visited Frida Kahlo’s home in Mexico City, I wasn’t prepared for how small and personal everything felt. The rooms aren’t grand. They don’t overwhelm you. They pull you in quietly.

Her bed sits there almost plainly, but once you understand what it represents, it’s hard to look at anything else. This is where she spent long stretches of her life immobilized. Where she painted while wearing corsets. Where mirrors were installed above her so she could paint herself lying down.

Standing there, I was reminded why Frida keeps pulling me back in, year after year. It isn’t just the imagery or the mythology—it’s her refusal to separate life from art. I’ve written before about the many ways she continues to shape how I think about painting, perseverance, and honesty in the studio in 5 Reasons I’m Inspired by Frida Kahlo, but seeing her bed in person made it feel more real. Frida didn’t wait for ideal conditions. She adapted. She painted where she was, with what she had, even when that place was a bed.

We talk so much about artistic vision, but this wasn’t conceptual. It was practical.

She painted in bed because she was sick. Because she was injured. Because chronic pain doesn’t politely wait for studio hours. The bed wasn’t symbolic at first—it was simply where she was.

Only later did it become part of the mythology.

Painting Because You Have To

Reading about the auction, I was struck by how often Kahlo’s work is described in terms of symbolism, surrealism, and metaphor. And yes—those layers are there. But I always hesitate when we start assigning too much intention to every object.

Sometimes artists don’t choose subjects for their symbolism. Sometimes they paint what’s in front of them. What’s within reach. What they’re living with.

Which brings me back to Frida—and back to Cézanne, too. I’ve written before about how people love to say artists pick objects because they “mean something.” But most of the time, artists paint what’s around them. Cézanne painted apples, bottles, cloth, and tables because that’s what was in his house and studio. He didn’t live by the sea. So no oysters.

Frida painted herself in bed because that’s where she was.

That doesn’t distinguish the work—it grounds it.

Why This Painting Matters Right Now

El sueño (La cama) isn’t one of Kahlo’s most reproduced images. She isn’t filling the canvas with her face. The skeleton—known in Mexico as a Judas effigy—hovers above her, tied with firecrackers, suggesting a passage between worlds. Sleep and death. Life and dreaming. Reality and something else entirely.

The art market loved it.

But what struck me was how humble the painting is, especially compared to other recent auction spectacles. No spectacle for spectacle’s sake, just a bed, a body, and the quiet tension of existing.

Julian Dawes of Sotheby’s said people feel a sense of connection to Frida—communion, even. I believe that. But I also think we feel something else: recognition.

She didn’t wait for ideal conditions to work. She adapted. She kept going.

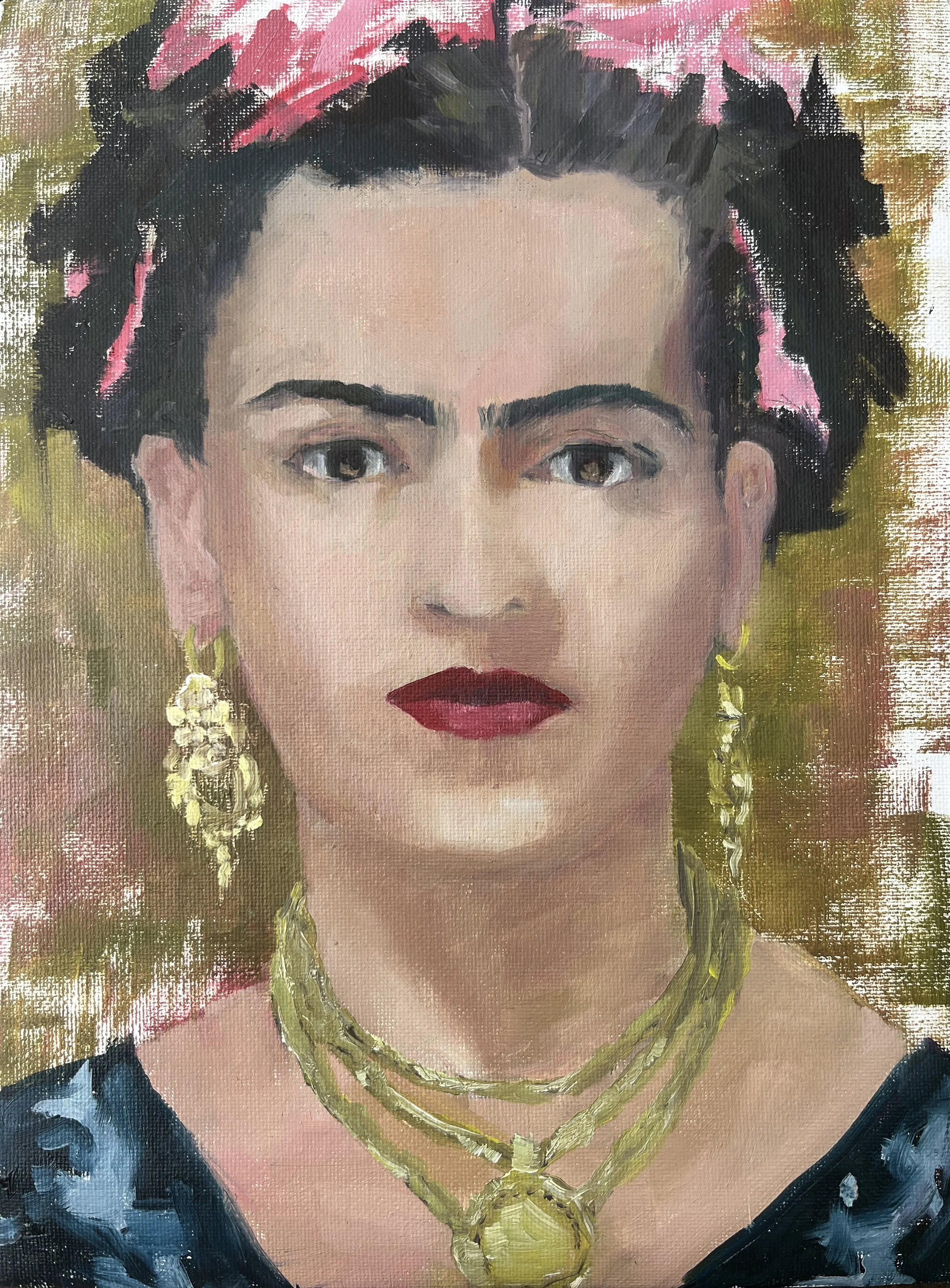

“Frida” - 12×9” - Oil on Canvas — My own ode to the artist and her famed self-portraits.

Painting Through Illness, Fatigue, and Limitation

I don’t paint in bed. But I think about limitation a lot.

There’s this fantasy that artists work best when everything is aligned—perfect light, uninterrupted time, strong bodies, endless energy. That hasn’t been my experience, and I don’t think it was Frida’s either.

Work happens in the middle of life. In messy studios. On days when the body isn’t cooperating. On days when focus comes in short bursts.

Frida’s bed wasn’t romantic. It was a workaround.

And somehow, that makes the work feel more alive to me, not less.

A Market Catching Up (Slowly)

The sale also says something important about the art market—something that’s been overdue.

Frida Kahlo’s rising auction prices aren’t just about pop culture. They reflect a broader reassessment of women artists, particularly those associated with Surrealism. Dorothea Tanning. Leonora Carrington. Leonor Fini. Gertrude Abercrombie. These names are finally being spoken in the same rooms where prices are set.

Still, it’s worth noting how rare Kahlo paintings are at auction. In 1984, the Mexican government declared her work a national artistic monument, banning any works located in Mexico from being exported. What appears on the market is scarce by design.

Scarcity fuels value—but so does relevance.

Why Frida Endures

Frida Kahlo’s work continues to resonate because it refuses distance. It doesn’t pretend the body is separate from the mind. It doesn’t hide pain behind polish.

She painted what she lived with: her injuries, her bed, her body, her marriage, her politics, her country.

And people feel that honesty, whether they can articulate it or not.

I’ve written before about Frida Kahlo in the context of the women around her—artists whose work was overlooked, overshadowed, or folded into larger movements without much credit. If you’re interested in that broader history, I explored it more deeply in a previous post, Kahlo and Mexico’s Forgotten Female Artists. Thinking about this record-breaking sale alongside that history makes the moment feel less like an isolated event and more like a slow, long-overdue shift.

Returning to the Bed

When I stood in her room at the Blue House, I didn’t feel like I was looking at a relic. I felt like I was looking at a workspace.

A place where decisions were made. Where things were tried. Where work happened anyway.

That’s what I keep thinking about now, after the headlines and the numbers and the records.

The bed wasn’t an idea. It was reality.

And from that reality, something lasting was made.

A Final Thought

Fifty-five million dollars is a staggering number. But the reason this painting matters has very little to do with money.

It matters because it reminds us that art doesn’t require ideal conditions. It requires persistence. Attention. A willingness to work with what you have.

Frida Kahlo painted from bed because she had to. And in doing so, she left us work that continues to speak—quietly, honestly, and without apology.